Classical Chinese poetry: a guide for the curious

Everything you need to start appreciating one of the most common traditional poetic forms in Chinese literature

In my last issue, I wrote at no small length about runes. This time I bring you something completely different. My goal with this issue is to get you as excited about classical Chinese poetry as I am. Although my formal education kindled within me a great love for English and Latin poetry, when I first encountered Classical Chinese poetry, I felt as if my eyes had been opened to a new world – I hope I can share some of that feeling with you here.1

I'm going to show you 登鸛雀樓 dēng guàn què lóu Climbing Stork Tower, a famous Tang dynasty poem, explaining how it works in the original language, in the hopes that you will see just how much gets lost in translation. (With classical Chinese poetry, more than usual gets lost!)

But before we get there, we have some linguistic and historical ground to cover…

Classical Chinese and Literary Chinese

Before we get started, we need to talk about what "the original language" means in the case of Classical Chinese poetry. Classical Chinese poetry is written in Classical Chinese – or, perhaps more accurately for much of the corpus, Literary Chinese.

What's the difference between the two? Indulge me in some definitions: Classical Chinese is the written language of a particular period of Chinese literature, lasting roughly from the late Spring and Autumn period through the end of the Han Dynasty. If your Chinese history is rusty, that's roughly the 5th century BC to the 2nd century AD.

Some of the great works produced during this period include 論語 Lúnyǔ The Analects of Confucius, 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mencius, 左傳 Zuǒzhuàn The Commentary of Zuo, and 史記 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian.

These works (among others of the era) had a foundational effect on Chinese civilization, and their style was emulated for centuries after – and, to some extent, still is!.

By the way, I'll be giving Chinese words and names in this format throughout this issue:

靜夜思 jìng yè sī quiet night thought

(traditional Chinese characters, pinyin romanization, gloss)

Although the language of the classic texts certainly derived from the spoken language at the time, the spoken language continued to change. But the way people wrote did not: they continued to emulate the classics, even as the way they spoke grew increasingly distant from the way they wrote.

But these later generations weren't perfect at emulating the classics, and changes from the spoken language nevertheless found their way into the written language. If we want to distinguish the written language of these later eras from the language of the classics, we can call the former Literary Chinese.

Nevertheless, given that the two varieties share so much, many people don't distinguish between the two and call them both Classical Chinese.

The language of all of the poems I'll be showing you today is more aptly termed Literary Chinese than Classical Chinese, but I'll be loose with my terminology and call it all Classical Chinese.

Pronunciation

When reading poetry in an ancient language, we typically prize the ability to pronounce the poems like their authors did – or at least to get as close as we can.

This helps us understand the literary devices the poet was using: the rhyme, the alliteration, the rhythm created by patterns of long and short vowels. These are all essential aspects of different poetic traditions. And there's no better way to understand them than to hear the way the poems sounded – at least, our best educated guess as to how they sounded.

Classical Chinese is different. Unlike most other ancient or historical languages, Classical Chinese texts are typically read using modern pronunciation. But why is this? And how is it even possible?

I’ll answer these questions by appealing to an example more familiar to readers of English, because this phenomenon isn’t unique to Classical Chinese. Take Shakespeare, for instance: although Shakespeare wrote in a form of English (Early Modern English, to be precise) removed from our own by four centuries of changes in sound (not to mention grammar and vocabulary), typically when we read Shakespeare, we read him in whatever dialect of 21st-century English we speak (to be precise, it’s usually one of the high-prestige standard varieties that is used). This ruins certain rhymes for us,2 but we don't let it bother us too much.3

This is the approximate situation with Classical Chinese poetry: it's typically not read to sound the same as when it was written.

But there's a crucial difference from the Shakespeare analogy that complicates the situation a bit. Unlike Early Modern English, Classical Chinese is written with Chinese characters. Chinese characters are a logography, where the units of the system represent words rather than sounds.4

English, by contrast, is written with an alphabet, where the units of the system do represent sounds, although in the case of English, sometimes the relationship between letter and sound is quite indirect!

This means that there are as many ways to read Classical Chinese as there are systems of reading Chinese characters: take, for example, the character 山, which represents a morpheme which we can gloss as 'mountain'. How do we read this?

We can give it the reading it has in Standard Mandarin, shān /ʂan55/, which is typically what is done. But Standard Mandarin is far from the only system of assigning readings to Chinese Characters. And not all of them are even varieties of Chinese/Sinitic languages: for example, you could use the Sino-Korean reading for 山, and say 산 /sʰan/.

You could even come up with a set of English readings, and read 山 as mountain. Japanese did something like this in developing the Japanese writing system, in part at least (although the full story is so much more complicated than I have time to discuss here – although it’s a good topic for another issue).

Reconstructions

Or you could do something that very few people do: you could treat Classical Chinese like we treat Classical Latin and try using a reconstructed pronunciation. But then the question arises: which one?

Because comparatively little phonological information is encoded in the writing system, reconstructions for Old Chinese (the spoken language that coincides with the written language that is Classical Chinese proper, as opposed to Literary Chinese) are much harder to make than for Latin or Ancient Greek, for example. But if you wanted to do this, you could choose a reconstruction (say, the Baxter-Sagart reconstruction), and pronounce 山 as /sŋrar/. Not a lot of people do this, though.

Alternatively, you might decide to try to emulate a later period, which gets easier, since we have much better data for later periods. In particular, we have works beginning in the 7th century5 that were meant as guides to reading classical texts.

The system described in these works, which scholars call Middle Chinese, probably didn't describe any one variety spoken at the time. But the Middle Chinese system ended up being used as the basis for what counted as valid rhymes in poetry for centuries afterwards.

The system described in these works, which scholars call Middle Chinese, probably didn't describe any one variety spoken at the time. But the Middle Chinese system ended up being used as the basis for what counted as valid rhymes in poetry for centuries afterwards.

Unfortunately for us, these works didn't directly describe how to pronounce things, at least not in a way we can straightforwardly interpret.

Instead, they showed us what sounded alike and what sounded different. But this is quite a lot of information to go on, especially given the fact that we have access to modern Chinese varieties.

Historical linguists can use these to triangulate what the works describing Middle Chinese might have been referring to, so the reconstructions of Middle Chinese don't tend to differ from each other to the same degree as the reconstructions of Old Chinese.

Choosing one of these reconstructions more or less at random (the Pulleyblank reconstruction, to be precise), our 山 would come out as /ʂəɨn/.

Modern Sinitic languages

I mentioned earlier that Classical Chinese is typically pronounced using readings from modern Mandarin,6 at least in the western world (and in much of China as well).

When it comes to poetry, however, Mandarin is ironically an odd choice. Due to the history of Mandarin, it's especially hard to hear many of the rhymes that would have worked in Middle Chinese. Let's dwell for a moment on why this is.

Mandarin is a tonal language, as are all modern Sinitic languages (aka Chinese dialects): this means that distinctions in pitch can affect what something means.

For example: Mandarin 馬 mǎ (with a low pitch) means horse, while 媽 mā (with a high pitch) means mother.

In the romanization we're using here, the difference in tone is notated by the different diacritic marks on top of the vowel (ā vs ǎ) – if you were wondering what all these markings on things like qièyùn were referring to, now you know.

Mandarin distinguishes between four main tone categories, which are notated as follows, using 'a' as an example vowel: ā (Tone 1: high), á (Tone 2: rising), ǎ (Tone 3: low/dipping), à (Tone 4: falling). Here's a paedagogical video which gives examples of how the Mandarin tones sound:

All other modern Sinitic languages have tones, but they don't have the same tones – or even the same number of tones.

Middle Chinese had tones too: four, to be precise. But the four tones of Middle Chinese do not cleanly map onto the four tones of Mandarin.

The four tones of Middle Chinese are conventionally called 平 píng level, 上 shǎng rising, 去 qù departing, 入 rù entering.7 The first three of the Middle Chinese tones are not too hard to map onto Mandarin tones:

平 píng level => Mandarin Tones 1 & 2, depending on the initial consonant

上 shǎng rising => Mandarin Tones 3 & 4, depending on the initial consonant

去 qù departing => Mandarin Tone 4

Although Mandarin tone 4 could correspond either to Middle Chinese 上 shǎng rising or 去 qù departing, that's not where the real trouble lies.

The real trouble lies in the fourth tone of Middle Chinese, the 入 rù entering tone. This tonal category is distinguished from the others not (just) by pitch, but also by the presence of a final stop consonant: -p, -t, or -k.

Here's where the problem comes in for reading poetry in Mandarin: in Mandarin all of these final stop consonants got deleted, and the syllables were reassigned into other tone categories, often unpredictably.

Take for example the following series of 入 rù entering tone morphemes, which rhymed in Middle Chinese:

桌 zhuō table = Middle Chinese /ʈaɨwk̚/8

覺 jué be aware = Middle Chinese /kaɨwk̚/

邈 miǎo distant = Middle Chinese /maɨwk̚/

Not only do these three morphemes all bear different tones in Mandarin, they also end in different vowels and diphthongs. You can see how this would play havoc with the rhymes!

Other Sinitic languages don't have this problem, at least not to the same degree. Here's what those four rhyming characters look like in Cantonese, for example:

桌 coek3 table

覺 gok3 be aware

邈 mok6 distant

They're not perfect rhymes anymore but they're a lot closer than they are in Mandarin.

One big difference between Mandarin and Cantonese in these morphemes is that Mandarin has totally lost the final -k that Cantonese has retained. I’ll return to this issue shortly.

Chinese metre

But first we need to talk about the metre. This is the real juicy stuff!

What is metre? Metre is the structure of a poetic line or a poetic verse.

Poetic traditions tend to favour or require certain metres. For example, for much of its history English has favoured the metre iambic pentameter, which features a rhythmic alternation of unstressed and stressed syllables (marked with an acute accent: á), like in these examples from Shakespeare:

So fóul and fáir a dáy I háve not séen. (Macbeth 1.3.40)

Shall Í compáre thee tó a súmmer's dáy? (Sonnet 18)

Chinese metre is totally different.

Of course, just as there are many metres used in the English poetic tradition (remind me to tell you all about Old English alliterative verse one day), there have been many different metres used in the Chinese poetic tradition.

But let's focus on one particularly famous and important kind: that used in 近體詩 jìntǐshī modern-style poetry.

First of all, 近體詩 jìntǐshī poems consist of either five or seven-character lines. I'm going to concentrate on five-character lines here so I don't obliterate my word count altogether.

Within a five-character line, there is a syntactic break between two unequal parts: this break, called a caesura (notated ||),9 occurs after the second character: xx||xxx.

Within the second half of the line, there's also a minor caesura (notated |) either before or after the fourth character, which creates another asymmetrical break.

We can notate the whole line as either xx||x|xx or xx||xx|x. These asymmetrical breaks, as well as the fact that the secondary caesura can appear in one of two positions, give this type of line a dynamic quality.

But don't take my word for it: let's look at an example (finally!). This one is from the poem 靜夜思 jìng yè sī quiet night thoughts by 李白 Lǐ Bái (701–762), which might be the most famous classical poem in China:

牀前||明月|光

chuáng qián || míng yuè | guāng

bed front || bright moon | shine

In front of the bed, the bright moon shines.

Notice how the line breaks at the caesura into two separate phrases that are unequal in length: 牀前 chuáng qián in front of the bed and 明月光 míng yuè guāng the bright moon shines. In the second half, we have another asymmetrical break between 明月 míng yuè the bright moon and 光 guang.

There is structure in 近體詩 jìntǐshī above the level of the line as well: lines are arranged into couplets which form a complementary whole (more on how they do this shortly).

Let's expand our field of view out to the whole first couplet of 靜夜思 jìng yè sī:

牀前||明月|光

chuáng qián || míng yuè | guāng

bed front || bright moon | shine

In front of the bed, the bright moon shines.疑是||地上|霜

yí shì || dì shàng | shuāng

suspect this || ground on | frost

(I) mistake this for frost on the ground.

Typically, poems rhyme on the second line of a couplet. Here the rhyme is established by 霜 shuāng frost. In 靜夜思 jìng yè sī, however, the first line of the poem also participates in the rhyme: 光 guāng shine (Middle Chinese /kwaŋ/) rhymes with 霜 shuāng frost (Middle Chinese /ʂɨaŋ/) – even in Mandarin!

Tonal metre

Now let's bring tones into the picture.

In 近體詩 jìntǐshī, you need to alternate between two different tonal categories 平 píng level, which consists (unsurprisingly) of the 平 píng tone, and 仄 zè oblique, which consists of the other three tones.

All the rules of tonal metre make reference to these two categories: level and oblique.

Now we see another reason why Mandarin can obscure the patterns of Classical poetry. As I mentioned earlier in the context of rhymes, the Middle Chinese tones map onto Mandarin tones in a rather complicated way. The first three, however, are simple:

The Middle Chinese 平 píng level tone corresponds nicely to Mandarin tones 1 and 2.

The Middle Chinese 上 shǎng rising tone corresponds to Mandarin tones 3 and 4.

The Middle Chinese 去 qù departing tone corresponds to Mandarin tone 4.

This means Mandarin tones 1 and 2 are 平 píng level for the purposes of poetic metre, and Mandarin tones 3 and 4 are 仄 zè oblique. Or, at least, it would mean that if the Middle Chinese entering tone (an oblique tone) couldn't show up as any of the four tones of Mandarin. Which unfortunately it does.

To get around this, I'll mark the entering tone words explicitly with a final p, t, or k, depending on the consonant they had in Middle Chinese: for example, 月 yuèt moon (rather than the expected Mandarin reading 月 yuè moon).

We'll consider these words all 仄 zè oblique for the purposes of poetry.

The rules

Now let's discuss the actual rules of tonal metre in 近體詩 jìntǐshī. Warning, there are lots of rules!10 If you want to skip the technical stuff and jump to the discussion of the poem, it’s in the next section.

Let's take them a few at a time:

Rule 1.11 There must be a sequence of two 平 píng level tones and a sequence of two 仄 zè oblique tones in a line. The fifth, "tie-breaking" syllable can have either a 平 píng level or a 仄 zè oblique tone.

Rule 2. The tie-breaking syllable can be placed either at the start of the line or the end of the line. If at the start, it will have the same tone as the next two syllables. If at the end, it will have a tone contrasting with the previous two syllables.

This leaves four possible lines:

Line 1. 仄仄平平仄

Line 2. 平平仄仄平

Line 3. 平平平仄仄

Line 4. 仄仄仄平平

But wait, there's more:

Rule 3. Lines in a couplet must contrast in their tones completely. For example, a couplet beginning 平平平仄仄 (Line 3) must end 仄仄仄平平 (Line 4).

Rule 4. All even lines must rhyme.

Rule 5. Rhymes must be in 平 píng level tone.

Taken together, these rules mean that couplets can only end with Line 2 (平平仄仄平) or Line 4 (仄仄仄平平). More than that, since couplets have to contrast in their tones completely, there are only two possible couplets:

Couplet 1. 仄仄平平仄 // 平平仄仄平 (Line 1 + Line 2)

Couplet 2. 平平平仄仄 // 仄仄仄平平 (Line 3 + Line 4)

Finally, there is a rule for what goes on between couplets as well.

Rule 6. The first two tones of the last line of a couplet should match the first two tones of the first line of the next couplet.

So when you put two couplets together, you can really only do it two ways:

Couplet 1 + Couplet 2. 仄仄平平仄 // 平平仄仄平 // 平平平仄仄 // 仄仄仄平平

Couplet 2 + Couplet 1. 平平平仄仄 // 仄仄仄平平 // 仄仄平平仄 // 平平仄仄平

And these are indeed the two standard tonal patterns for 近體詩 jìntǐshī quatrains.12

If you're thinking this sounds a bit limiting, don't worry: there's an escape hatch. You can optionally rhyme both lines of the opening couplet. Since Rule 5 forces rhymes to be on 平 píng level tones, this means that Rule 3, which forces the two lines of a couplet to be fully contrastive in their tones, has to be loosened.

Instead, Lines 2 and 4 (in either order) can form a rhyming couplet. These are the variant couplets:

Variant Couplet 1: 仄仄仄平平 // 平平仄仄平 (Line 4 + Line 2)

Variant Couplet 2: 平平仄仄平 // 仄仄仄平平 (Line 2 + Line 4)

You're only allowed to do this if it's the first couplet of the poem!

With this, we have the full set of four possible tonal patterns for 近體詩 jìntǐshī quatrains:

Standard Quatrain 1. Standard Couplet 1 + Standard Couplet 2.

仄仄平平仄 // 平平仄仄平 // 平平平仄仄 // 仄仄仄平平

Standard Quatrain 2. Standard Couplet 2 + Standard Couplet 1.

平平平仄仄 // 仄仄仄平平 // 仄仄平平仄 // 平平仄仄平

Variant Quatrain 1. Variant Couplet 1 + Standard Couplet 2.

仄仄仄平平 // 平平仄仄平 // 平平平仄仄 // 仄仄仄平平

Variant Quatrain 2. Variant Couplet 2 + Standard Couplet 1.

平平仄仄平 // 仄仄仄平平 // 仄仄平平仄 // 平平仄仄平

Now we are at long last ready to confront – or rather, appreciate – a full poem.

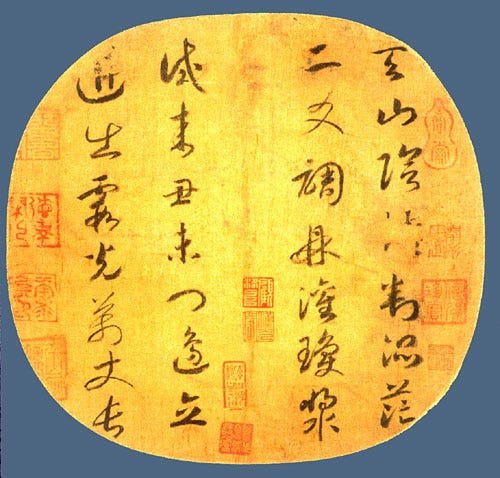

登鸛雀樓 dēng guàn què lóu Climbing Stork Tower

The poem I've chosen is 登鸛雀樓 dēng guàn què lóu Climbing Stork Tower by 王之渙 Wáng Zhīhuàn (688–742). Here it is in full.

白日||依山|盡

báik rìt || yī shān | jìn

white sun || rest mountain | come.to.end

The white sun rests on the mountains and vanishes.黃河||入海|流

huáng hé || rùp hǎi | liú

yellow river || enter sea | flow

The Yellow River flows into the sea.欲窮||千里|目

yùk qióng || qiān lǐ | mùk

want reach.limit || thousand li | sight

(If you) want to see for a thousand li,13更上||一層|樓

gèng shàng || yīt céng | lóu

again climb || one story | tower

Climb another story of the tower.

Before I (briefly) discuss the contents, let's look at the tone pattern:

白日依山盡

báik rìt yī shān jìn

仄仄平平仄黃河||入海|流

huáng hé rùp hǎi liú

平平仄仄平欲窮||千里目

yùk qióng qiān lǐ mùk

仄平平仄仄更上||一層樓

gèng shàng yīt céng lóu

仄仄仄平平

But for one syllable, this is Standard Quatrain 1. Can you find the syllable that doesn't fit? (scroll down to get the answer)

…

…

…

It's 欲 yùk want, at the beginning of Line 3. The tone pattern 仄平平仄仄 is not one of the few prescribed 近體詩 jìntǐshī lines. 平平平仄仄, however, with a level tone in first position, would be what we expect given "the rules".

But rules are meant to be broken, aren't they? Or at least bent. Often the first or third character in a 近體詩 jìntǐshī line will appear with the "wrong" tone. This is considered an acceptable kind of variation, just like an iambic pentameter line can often start with a trochee (stressed then unstressed) rather than an iamb (unstressed then stressed).14

Parallelism

What about the contents? I won't say too much about what the poem means, but notice that there's something interesting going on here too.

Within both couplets, we see that each character of the first line parallels in some way its corresponding character on the second line.

At the very least this parallelism involves part of speech: nouns match nouns, verbs match verbs, and so on. But it goes farther than that. Colours correspond to colours (白 báik white vs 黃 huáng yellow), nouns referring to elements of nature match other such nouns (日 rìt sun vs 河 hé river), units of measurement mirror each other (里 lǐ li vs 層 céng storey).

This parallelism is a common feature of Classical Chinese verse. The ways Chinese poets use – or don't use – parallelism is a major source of the interplay of creativity and constraint that brings such delight to poetry.

And with that, I rest my case: I hope I've convinced you that Classical Chinese poetry is worth a deeper look. If you want to learn more, check out the book How to Read Chinese Poetry (2008) by Zong-qi Cai or the companion video podcast.

Appendix: 靜夜思 jìng yè sī quiet night thoughts

Since I mentioned it earlier, here is the poem 靜夜思 jìng yè sī quiet night thoughts by 李白 Lǐ Bái in its entirety:

牀前||明月|光

chuáng qián || míng yuèt | guāng

bed front || bright moon | shine

In front of the bed, the bright moon shines.疑是||地上|霜

yí shì || dì shàng | shuāng

suspect this || ground on | frost

(I) mistake this for frost on the ground.舉頭||望|明月

jǔ tóu || wàng | míng yuèt

raise head || look | bright moon

(I) raise my head and look at the bright moon.低頭||思|故鄉

dī tóu || sī | gù xiāng

lower head || think | old hometown

(I) lower my head and think of my hometown.

As you can see, this is a quatrain. But which of the four 近體詩 jìntǐshī possible quatrains? Let's examine the tones.

牀前明月光

chuáng qián míng yuèt guāng

平平平仄平疑是地上霜

yí shì dì shàng shuāng

平仄仄仄平舉頭望明月

jǔ tóu wàng míng yuèt

仄平仄平仄低頭思故鄉

dī tóu sī gù xiāng

lower head think old hometown

平平平仄平

Famous quatrain though it is, this poem is not a good example of a 近體詩 jìntǐshī quatrain. None of the four lines of this poem matches any of the tonal templates allowed by the verse form.

My thanks to Prof. Ken Cheng for helping me understand some of these issues. Any faults in the discussion are mine alone!

Poets of past ages didn't always rhyme perfectly: not every rhyme in Shakespeare that we find imperfect rhymed perfectly for Shakespeare, say. But some did. See this blog post by A. Z. Foreman on this issue.

Unless, of course, you're one of the devotees of "Original Pronunciation", who aim to approximate Shakespeare's pronunciation in their performances.

This is a simplification: Chinese characters actually represent morphemes rather than words, and they do encode some phonological information, albeit in a rather indirect manner.

Beginning, at least as far as we are concerned, with the 切韻 qièyùn dividing sounds (AD 601). Earlier works like it existed but did not survive to the present.

Specifically, the standardized variety that makes up the official language of China.

The four tones of Middle Chinese are often reconstructed as follows (using Chao tone numbers, where 5 is high pitch and 1 is low): 平 píng level (33), 上 shǎng rising (35), 去 qù departing (51), 入 rù entering (33), but with a final stop consonant.

Pulleyblank reconstruction.

Caesurae exist in many metres beyond the 近體詩 jìntǐshī line.

I owe this way of understanding the rules of 近體詩 jìntǐshī to Cai (2008). How to Read Chinese Poetry.

Confession: I made up these rule numbers.

絕句 juéjù cut lines

A 里 lǐ li is a unit of measurement; during the Tang dynasty (when the poem was written), it measured 323m.

This is called inversion: an example can be found in Nów is | the wín|ter óf | our dís|contént. (Richard III 1.1.1)

I’ve studied Classical Chinese off and on for more than two decades. I’m much better at reading modern Chinese for sure. Reading the poems brought back some memories. I’ve often heard the last two lines of the first poem you wrote about are often quoted to indicate ever striving for further improvement.

Hmmm, looking at 靜夜思 I notice that in Mandarin lines one, three and four rhyme but do not have the same tones, however in Cantonese lines one three and four have the same tone and have the same end rhyme.

I will have to read your article more carefully because there is some interesting thing