At the beginning of December, I gave a workshop on the runic alphabets, and as I prepared my material I was struck by the fact that the internet is a terrible place to learn about runes. [Edit: Not as bad as it used to be, thanks to Jackson Crawford]

The signal-to-noise ratio for someone who has a linguistic or historical interest in the runic alphabets is extremely low (low is bad, right?).

Over the next few issues, I’ll give a summary of what I wish I’d read about runes when I first got interested in the topic, including the questions I find most fascinating today.

What are runes?

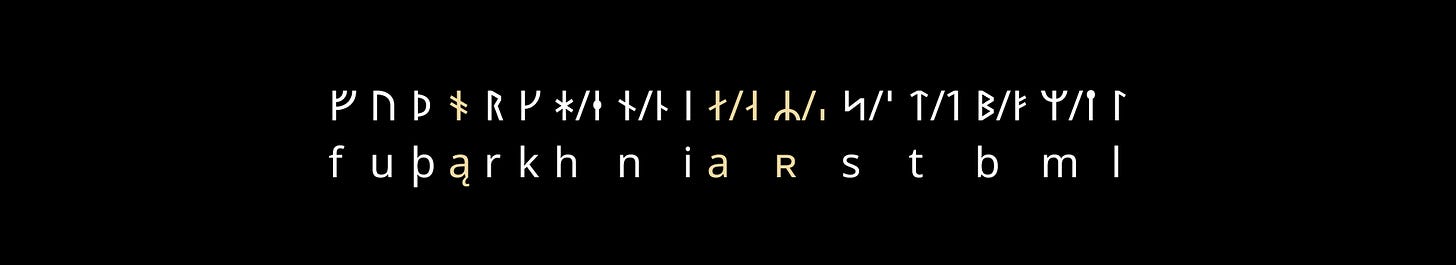

We can define a rune as any of a collection of related alphabets used to write various early Germanic languages. If you haven’t seen them before, here’s an example of one runic alphabet:

It’s important to note that runes are not a language in themselves. A particular runic alphabet can in principle be used to write many different languages, although particular runic alphabets tend to be associated with particular languages. For example, the Codex Runicus pictured above contains a late runic alphabet (Mediaeval Runes) which writes the Old Danish language.

Etymology of rune

The word rune has an interesting history in English. A word rūn ‘secret, mystery; rune’ is found in Old English, but the Modern English word rune entered the language in the 17th century, likely either from post-classical Latin rūna (itself a loan from some early Germanic language), Icelandic rún, or its cognate in a modern Scandinavian language (e.g., Danish and Norwegian rune, or Swedish runa). Perhaps it entered English by more than one of these routes; it’s a mystery (aren’t you glad I didn’t say rune?).

Old English rūn is continued in Middle English roun,1 which would probably rhyme with down if it still existed today. Roun had a wide range of meanings extending from ‘secret, mystery’ to ‘(secret) deliberation, counsel’ to ‘utterance, conversation’ to ‘song’ to ‘language’. There is also a set phrase in roun ‘in secret’ which I’d very much like to bring back into currency.

The OED remarks that the precise sense of roun is often difficult to discern, given that its usage was mostly confined to poetry, for example:

Somer is comen wiþ loue to toune, // Wiþ blostme, and wiþ brides roune.

Summer has come with love to town, // With blossom and with brides’ roun.

before 1300, Thrush & Nightingale (Digby) l. 2 in C. Brown Eng. Lyrics 13th Cent. (1932) 101 (MED)

Here the OED interprets roun as ‘cry, song’, but it’s easy to see how other interpretations are possible.

Other Germanic languages show cognates as well: in Swiss German, there is – or was? – a word Raune, which is a type of vote given by whispering into the ear of a magistrate. Middle Low German reports a set phrase mid rūne und rāde, meaning ‘in secret deliberation’. Even English has a related, albeit archaic verb round, meaning ‘whisper’!

Looking back at the earlier history of the rune word, we can trace back the various early Germanic forms to a Proto-Germanic *rūnō ‘secret, mystery; rune’. What’s striking about this form is that very similar forms are found in Celtic languages: Modern Irish even has rún ‘secret, mystery’, continuing Proto-Celtic *rūnā.

Given the strong similarities between the Celtic and Germanic words in both form and meaning, a relationship is impossible to deny. But the nature of the relationship is still cloudy. Are the Celtic and Germanic forms cognate? Or was this an instance of borrowing from one to the other? If so, which was the source and which the recipient?

Whatever the answer, the extension of the semantic field to ‘rune’, i.e. character in the runic alphabet, only happened in Germanic.2 Outside of the Germanic and Celtic families, connections have been made with the Latin rūmor ‘rumour; rustling, murmur’, which has been traced back to a Proto-Indo-European root *rewH- ‘roar’. If this derivation is accurate, I’d love one day to hear the tale of how a roar became no more than a whisper.

There’s an idea out there that the joining of the two broad fields of meaning ‘secret, mystery’ and ‘rune’ arose from the accidental collision of two originally separate words, on the argument that the runes probably didn’t represent any great secret or mystery.3

Whether or not the association between the meaning ‘secret, mystery’ and the meaning ‘character in a runic alphabet’ arose because the runes were first thought of as secret, mysterious things, runes today have certainly inherited this association. Indeed, more than mere mystery and secrets, the thing the runes are most linked to today is magic. But how far back does this relationship go?

Runic magic

Often, when reading popular books about runes, you will read that runes have been intimately associated with magic since their earliest days. And it is true: there is evidence that runes were linked with magic from the earliest days of their use – or, at least, from the earliest evidence we have of their use. Unfortunately, much of this evidence is difficult to interpret. My aim is not to debunk the notion that runes were magical from early times, but rather to show you the kind of evidence we do have and let you decide for yourselves whether you’re convinced.

The evidence falls into a few categories:

Nonsense sequences in early inscriptions.

The terms alu and erilaz in early inscriptions.

Tacitus’ remarks in Germania.

The content of certain runic inscriptions.

Later traditions.

One type of evidence comes from some early runic inscriptions, containing apparently nonsense sequences of sounds, which scholars have interpreted as “magic words”.

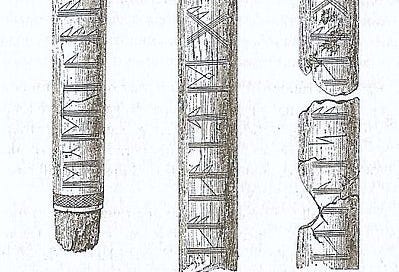

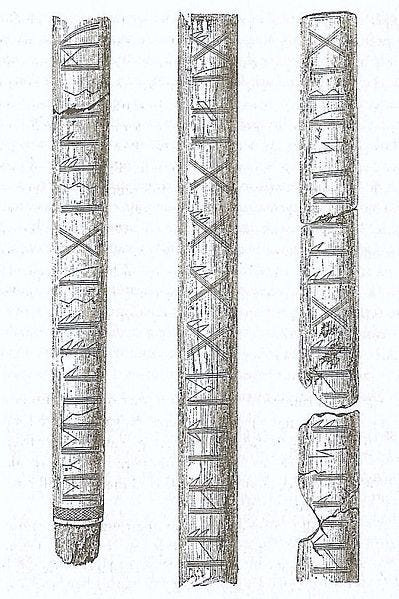

For example, Kragehul I, which is a lance shaft found in Denmark likely dating from the 5th century AD, bears an inscription which begins: ek e͡rila͡z asugisalas m͡uh͡a h͡aite g͡ag͡ag͡a4 I, the erilaz of Āsugīsalaz,5 am called Muha: gagaga.

We’ll return to what an erilaz is shortly. For now let’s focus on gagaga.

It is often compared to similar nonsense phrases in other inscriptions, for example g͡æg͡og͡æ on the Undley bracteate (5th century AD, England) and tuwatuwa on the Vadstena bracteate (circa AD 500, Sweden).

These nonsense phrases are often interpreted as magical chants: compare our own abracadabra, alakazam, etc. Clearly, however, this isn’t the most direct evidence for the magical use of runes.

A different form of evidence comes from the presence and meaning of certain words in these early inscriptions, in particular, alu and erilaz.

The word alu (alu ᚨᛚᚢ) appears in many early inscriptions (from the 3rd–8th centuries AD) especially in Scandinavia, alone or within a larger inscription. The word alu seems either literally to mean ‘ale’ or at least to be related to the word for ale (reconstructed for Proto-Germanic as *aluþ). At any rate, the relationship with the Modern English word ale isn’t hard to see.

On these inscriptions, however, alu must have meant something more: it often appears on its own, along with a god’s name, or at the end of a nonsense phrase. Later on, in the Old Norse poem Sigrdrífumál (13th century at latest, Iceland), the hero Sigurðr is taught by the valkyrie Brynhildr about the use of ölrúnar ‘ale-runes’ in the context of other types of runes, or other names for runes (‘speech-runes’, ‘victory-runes’, ‘birth-runes’, etc.):

19. Beech-runes are there, birth-runes are there, And all the runes of ale. (And the magic runes of might;) Who knows them rightly and reads them true, Has them himself to help; (Ever they aid, till the gods are gone.)6

So it is clear that, by this point, the association of runes with magic is established: if someone “who knows them rightly and reads them true, has them… to help”, they must have some magical power. But are these ölrúnar ‘ale-runes’ referring to the same practice as the much earlier alu inscriptions? If so, Sigrdrífumál may represent the continuation of a very long tradition.

Another word of interest in this regard is erilaz. We saw this word earlier in the Kragehul I inscription, which can be translated as I, the erilaz of Asugisalaz, am called Muha: gagaga.

What is an erilaz? It is a word used often in runic inscriptions to identify the author of the inscription, as it does in the case of Kragehul I, where the erilaz is apparently someone named Muha. For this reason, erilaz has traditionally been interpreted as meaning ‘someone who uses runes’, especially for magical purposes, given that the term shows up so often on runes which look – for the reasons stated above – magical.

But it is by no means certain that erilaz was a term for a magical practitioner. The scholar Bernard Mees has argued that erilaz referred to a member of a particular social class “of middling rank within the early Germanic nobility”.7 In other words, they weren't rune specialists, but rather people rich enough to be able to afford jewellery to inscribe runes on.

Consdering erilaz a term for a particular rank makes sense if it is related to the word *erlaz ‘a member of the nobility’, the ancestor of Modern English earl. The argumentation is a bit technical, and hinges on whether it makes sense for there to be two variants of the same word, one with an -i- in the middle and one without it. It’s not a typical alternation for words of this shape, but Mees finds enough parallels to make it at least plausible that an erilaz was not in fact a term for a magical practitioner.

We also have the testimony of Tacitus, who described in Germania 10… something. Whatever this was, there’s no doubt it was magical. But was it runes?

Augury and divination by lot no people practise more diligently. The use of the lots is simple. A little bough is lopped off a fruit-bearing tree, and cut into small pieces; these are distinguished by certain marks (notis quibusdam), and thrown carelessly and at random over a white garment. In public questions the priest of the particular state, in private the father of the family, invokes the gods, and, with his eyes towards heaven, takes up each piece three times, and finds in them a meaning according to the mark previously impressed on them. If they prove unfavourable, there is no further consultation that day about the matter; if they sanction it, the confirmation of augury is still required. For they are also familiar with the practice of consulting the notes and the flight of birds.8

It all depends on what exactly Tacitus meant by “certain marks”. Were these runes? If so, it is curious that no other early evidence mentions divination as a use of runes. All the other early evidence for runic magic seems to traffic in things like magical protection and curses (for which, read on).

While on the subject of early evidence of runic magic, there are a few objects worth noting where a magical interpretation seems likely. Among them are a series of rings (for example, the Kingmoor ring; 8th–10th centuries, England) whose inscriptions stubbornly resist interpretation. Inscriptions that resist interpretation are often taken by scholars as evidence of magic. I’ll remain mostly silent on the question of whether this is a good methodological assumption.

More convincing, perhaps, are the objects whose runic inscriptions are unambiguously curses. Take, for example, the Stentoften Runestone (6th–7th century, Sweden), whose inscription reads (in transcription):

[…] haidiz runono, felh eka hedra ginnurunoz. Hermalausaz argiu, Weladauþs, sa þat briutiþ.

‘[...] I, master of the runes, conceal here runes of power. Incessantly (plagued by) maleficence, (doomed to) insidious death (is) he who this breaks.'9

That exhausts the early evidence. The later evidence is much more explicit: we have mediæval texts that explicitly mention runic magic. The most important I have mentioned already, the Old Norse poem Sigrdrífumál (part of the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century). Sigrdrífumál has runic magic as a major theme.

Sigrúnar þú skalt kunna,

ef þú vilt sigr hafa,

ok rísta á hialti hiǫrs,

sumar á véttrimum,

sumar á valbǫstum,

ok nefna tysvar Tý.Victory runes you must know

if you will have victory,

and carve them on the sword's hilt,

some on the grasp

and some on the inlay,

and name Tyr twice.10

If carving runes into a sword’s hilt to ensure victory isn’t magic, I don’t know what is. Here at last is clear evidence that, at least by the 13th century, there was an association between runes and magic.

From what I’ve shown you so far, however, I believe it’s fair to say: the question remains of just how ancient that association is!

This association, of course, was revived in the 20th century in connection with Germanic mysticism and, later, contemporary magical and divination systems (e.g. the runes you can buy at the bookstore), which is how many people first come across runes today.

Runic alphabets as writing systems

Of course, merely because runes were used for magical purposes, that doesn’t mean that they didn’t have other, more prosaic uses. They were, after all, part of a writing system. Or rather, writing systems, plural.

There were several runic alphabets, each of which was used in a different time and place, and each of which worked a bit differently. The big three are: the Elder Futhark, the Younger Futhark, and the Anglo-Saxon or Anglo-Frisian Futhorc.

The name Futhark comes from the first six runes in the alphabet in its conventional order, which are conventionally transcribed as <f u þ a r k>, where þ represents the th sound as in thing.

Most public attention has collected around the Elder Futhark alphabet – as Jackson Crawford has speculated, this may be because the name “Elder Futhark” simply sounds cool. When you buy a runic divination kit in the bookstore, it will most likely be using the Elder Futhark alphabet.

As the name suggests, the Elder Futhark is the oldest of the runic alphabets. Just how old? The Elder Futhark was used from the 2nd to the 8th centuries AD.11

We have a good idea of the runes used in the Elder Futhark alphabet as well as their order, because writing out the complete alphabet was something people liked to do. In fact, many inscriptions are nothing more than the runes written out in order.

Here’s something that surprises many people: the language Elder Futhark wrote is not the Old Norse of the Viking Age. The Elder Futhark texts are actually in an older form of the language often called Proto-Norse.12 In fact, it's not clear that the language the oldest of these texts are written in represents an ancestor of only Old Norse, as opposed to Old English or Old High German. But the name has stuck.

What’s the difference between Proto-Norse and Old Norse? Quite a bit! Proto-Norse phonology is very similar to the system reconstructed for Proto-Germanic, the hypothetical ancestor of all Germanic languages. Compare the Proto-Norse word for ‘guest’ gastiz (used as part of a name in the inscription ek hlewagastiz holtijaz horna tawido ‘I, Hlewagastiz of Holt, made this horn’) with the Old Norse gestr ‘guest’.

The other runic alphabets are developments of the Elder Futhark, with some runes lost, added, changed, or adapted for use in representing a changed language.

The Younger Futhark developed out of the Elder Futhark in Scandinavia around the 8th century AD. This means that the Younger Futhark is the alphabet used to write Old Norse, the language of the Viking Age (from the late 8th century to the middle of the 11th century).

Apart from the fact that a few runes (marked in yellow above) are now associated with different sounds, the immediately obvious difference between the Elder and Younger Futharks is that the Younger Futhark has far fewer runes: the Younger Futhark has 16 runes, while the Elder Futhark has 24. At the same time, the language the runes were used to write also changed, but in the opposite direction: Old Norse had more sounds that needed to be distinguished from one another than did Proto-Norse.

These two facts put together mean that the Younger Futhark was an extremely defective writing system: defective in a technical sense, in that not all the contrasts relevant from the language show up in the writing system. In a defective writing system, different-sounding words are spelled the same way.13 Why did they reduce the number of runes at the very stage when they needed more runes? Another runic mystery.

How did this work in practice? Simply put, one rune could stand not only for the sound its ancestor stood for in the Elder Futhark, but also for similar sounds. So the rune ᚴ (transcribed <k>) is used not only for the sound /k/ (as in cat) but also for the sound /g/ (as in good). Similarly, the rune ᚢ (transcribed <u>) could mean an /u/ vowel (as in food), an /o/ vowel (somewhat like in go), or one of several other sounds.

Another thing you may have noticed about the Younger Futhark is that several runes have two forms. This represents the fact that the Younger Futhark came in two styles: long-branch (forms on the left) and short-branch (forms on the right). Short-branch runes were popular, especially in Sweden.

Later, after about the year 1000, the Younger Futhark system developed optional ways to sort out some of the ambiguity in what rune stands for what sound. Runes were repurposed, new “accented” runes were created by adding dots, and some short-branch forms were used to restore some of the distinctions lost in Younger Futhark. But that’s a story for another day.

The Anglo-Saxon Futhorc also grew out of the Elder Futhark, but it did not share the Younger Futhark’s minimalist sense of design. The Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, by contrast, enlarged the number of runes in the system.

At first, only a few new runes were added, but later other runes appear – although in the case of the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, we don’t appear to have a single list of all the runes used in the alphabet.

The lists we have differ in what runes they consider part of the alphabet, and we also find runes used in manuscripts and inscriptions which are not listed in any of the rune lists. As above, I’ve marked the runes whose sounds changed in yellow. The new runes added by the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc are coloured blue.

Ok, enough about runes now

I hope you’ve enjoyed this not-so-brief introduction to the runic alphabets. Runes are much misunderstood and mythologized, but there’s enough mystery in runes as they actually were to sustain a lifetime of curiosity. And that’s without touching on the origin of the runic alphabets – perhaps a topic for another month’s post.

Middle English forms are notoriously variable, so you’ll see in texts the variants run, ron, rone, rune, roun, roune, rowne, and more besides.

Connections have been also sought within the Germanic family, and some candidates have been found in various words which might plausibly have arisen from the same Germanic base: Old English rēonian ‘to conspire’, rēoniġ ‘gloomy’, rēonung ‘muttering’; Middle High German rienen ‘to lament’; and the Norwegian dialectal form rjona ‘to babble’.

The name to know here is Richard L. Morris.

The marks joining the letters indicate bind runes. Bind runes are ligatures wherein two or more runes are joined to form a single rune. An example of a ligature in the Roman alphabet is <æ>, where <a> and <e> are joined into a single letter.

Āsugīsalas, literally ‘of the god-pledge’, from *ansuz ‘god’ and *gīs(a)laz ‘pledge, hostage’.

Trans. Bellows (1937).

Mees (2003: 59).

Complete Works of Tacitus. Tacitus. Alfred John Church. William Jackson Brodribb. Lisa Cerrato. edited for Perseus. New York. : Random House, Inc. Random House, Inc. reprinted 1942.

Transcription and translation courtesy of the Scandinavian Runic-text Data Base, admittedly accessed through the easier means of Wikipedia.

Trans. Jansson (1987: 15).

Hot off the press: maybe even earlier, a recent runestone find has been dated between AD 1–250 (source). If the earlier end of this range ends up being accurate, we’ll have to adjust the dates we’re used to giving.

The term Proto-Norse is not a very good one, since proto-languages are usually understood as reconstructed, rather than attested. But the existence of the Elder Futhark inscriptions means this is an attested language, so Proto-Norse is a strange choice for a name. Nevertheless, it has stuck.

Don’t take it personally, Younger Futhark: English orthography is defective in this way too. Otherwise, you wouldn’t write wind (as in Inherit the Wind) using the same four letters you use to write wind (as in wind up in a hospital on Guerrero St.).

Thank you, Colin, for this beautifully written and researched intro to runes!

The thing you noticed, that "the internet is a terrible place to learn about runes", stands true about any endeavor of learning about specialized terms, in any specialized field of study and/or practice

I unhappily made the same observation when checking the first 12 pages (first 120 results) about "Product Strategy" (specialized term from the field of Product Development) - most of these results, about 90%, are low quality, copy-pasted, promo websites (trying to sell a course, an app etc) or outright junk.

That is why one way I discovered for actually learning relevant things in specialized fields is to connect, follow, support, study bodies of work of researchers & practitioners in these fields. The term coined for this by the Learning & Development professionals is "people-based learning"

I am grateful for everything that you share, every edition is illuminating. Thank you!

Very interesting read. One thing that struck me is the word gagaga and the common ending with the unidentified tribes/areas of Oht gaga and Nox gaga in the Tribal Hideage